If not for the quick thinking of a test pilot 50 years ago, the entire F-16 program might have been ruined during its first performance demonstration flight. The incident took place on 20 January 1974, when test pilot Phil Oestricher climbed into the cockpit of the General Dynamics YF-16 prototype at Edwards Air Force Base, California. His mission that morning was straightforward: to perform a high-speed taxi test where the aircraft would move under engine power alone along the runway, without taking off—simply to demonstrate engine thrust. At that time in 1974, the YF-16 was brand new, having been publicly unveiled just over a month earlier. The first flight using the new flight control system was not scheduled until early February 1974.

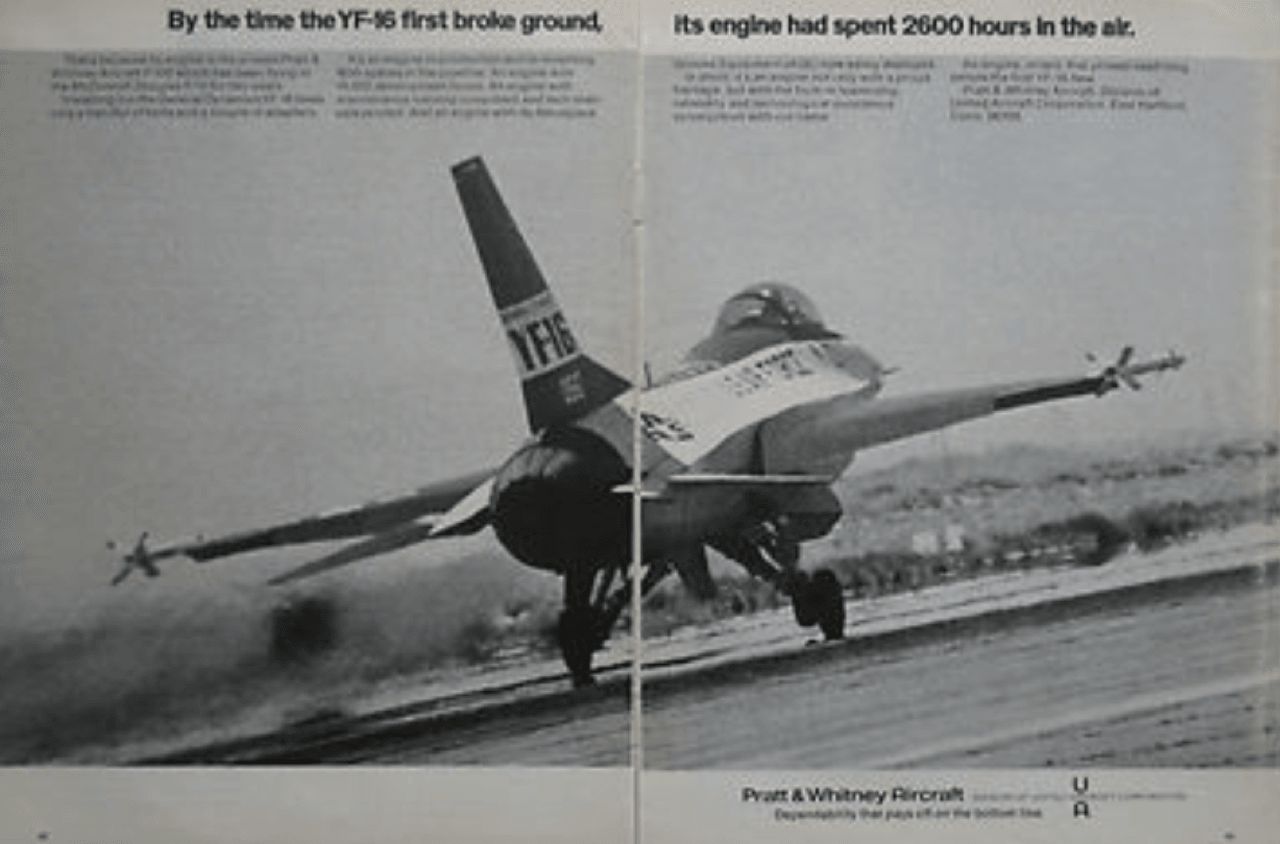

The high-speed engine run of the Pratt & Whitney PW100 seemed like an easy task for the fresh prototype. However, as Oestricher slightly raised the aircraft's nose, the YF-16 suddenly tilted violently, causing the left wing and right tailplane to slam onto the runway with a loud crash. A columnist for the Seattle Post Intelligencer reported on the near-disastrous first run: "As Oestricher struggled desperately to control the uncontrollable aircraft, the situation worsened as the YF-16 began veering left."

Oestricher knew that if he continued to let the situation go unchecked, disaster was imminent. He aborted the planned high-speed taxi test and, as the aircraft became nearly uncontrollable, he changed tactics—he pushed the throttle to full power and immediately raised the nose to lift off before the swaying test plane could roll over.

After a tense moment, the aircraft’s nose lifted and then settled back onto the runway—Oestricher accelerated enough to lift the prototype into the air for its first flight, which lasted six minutes before a safe landing.

Thanks to Oestricher’s exceptional piloting skills, a looming catastrophe was averted. The first ascent of the "Viper" amazed spectators. Since then, due to its performance and reliability, the F-16 has become one of the most successful fighter jets remembered by the current generation. Fifty years later, over 4,600 F-16s have been produced, with manufacturing ongoing.

At virtually any time of conflict, day or night, there is a high chance that an F-16 is flying somewhere in the world amid territorial disputes. Since entering service with the U.S. Air Force in 1978, the F-16 has been sold to and operated by 25 other air forces, from Norway to Chile and Morocco to Thailand. By 2026, 47 years after entering service, over 2,000 F-16s remain actively flying worldwide.

Designed as a small, lightweight, and highly maneuverable fighter, the F-16 is now used in a broad range of missions, including ground attack, anti-ship, aerial reconnaissance, and suppression of enemy air defenses. Since 2015, the F-16 has been the most numerous fixed-wing fighter globally, with an estimated 2,000 still in service worldwide.

The Lockheed Martin F-16 AM/BM Block 15 eMLU is Thailand’s modernized fighter jet, featuring a Mid-Life Upgrade (MLU). The main variants, AM (single-seat) and BM (two-seat), are upgraded from the original Block 15 models to match the capabilities of F-16C/D Block 50/52. The comprehensive upgrade enhances multi-role combat ability with modern electronics, new radar, Link 16 systems, and support for new weapons such as JDAM precision-guided bombs and AIM-120 missiles, strengthening national defense capabilities.

Key features and improvements:

MLU (Mid-Life Upgrade): A major overhaul that brings older aircraft up to the capabilities of newer models.

Radar system: Installation of more advanced radar technology.

Link 16 system: Enhanced tactical data exchange capabilities.

IFF (Identification Friend or Foe) system: Improves accurate friend or foe identification.

Weapons: Supports modern armaments such as JDAM precision-guided bombs and AIM-120 AMRAAM air-to-air missiles.

ECM pod: Capability to equip electronic countermeasure pods like the ALQ-131 for self-defense.

Maneuverability: A compact, single-engine fighter with high agility, using fly-by-wire control systems.

The F-16’s design integrates advanced aerospace engineering and proven systems from aircraft like the F-15 and F-111, blending them to reduce complexity, size, cost, maintenance, and weight. The airframe is lightweight without sacrificing strength. With full fuel, the F-16 can withstand up to 9 Gs—nine times Earth’s gravity—surpassing many current fighter aircraft.

The cockpit features a clear bubble canopy providing pilots with 360-degree visibility and excellent forward and upward views. Side and rear visibility are also improved. The seatback angle was increased from 13 to 30 degrees to enhance pilot comfort and G-force tolerance. Pilots control the F-16 smoothly via a fly-by-wire system, which replaces traditional cables with electronic signals for precise handling during high-G maneuvers. The side-stick controller replaces the conventional center stick, sending electrical commands to flight control surfaces.

The ACES II ejection seat is rocket-powered and mounted at a 30-degree angle, compared to the 13–15 degrees typical in older fighters. This steeper angle helps pilots withstand G-forces better and reduces blackout risk during sudden G-load changes. However, it increases neck injury risk if headrests are not used. Later models reduced the seat angle to about 20 degrees. The thick polycarbonate canopy requires the seat to jettison it before ejection, unlike other jets that break the canopy with a metal spike if necessary.

Pilots operate the aircraft with a right-hand side-stick and left-hand throttle, with numerous switches relocated to the stick for ease under high-G conditions. The side-stick sends electronic signals via fly-by-wire to the flight control computer (FLCC). Originally fixed, the stick was later allowed slight movement to reduce pilot fatigue and overcontrol during takeoff. The HOTAS (Hands On Throttle And Stick) concept, first used on the F-16, has become a standard in modern fighters, despite side-stick controllers not being universally adopted.

The F-16 cockpit includes a HUD (Head-Up Display) projecting flight and combat data as symbols directly in the pilot’s line of sight without blocking visibility, aiding situational awareness. Boeing-developed JHMCS (Joint Helmet Mounted Cueing System) helmets, installed on Block 52 models, allow pilots to control short-range missiles like the AIM-9X by targeting where they look, even outside the HUD’s view. This system was first used operationally during the Iraq Liberation campaign.

Pilots receive additional information via Multi-Function Displays (MFDs). The left MFD shows primary flight data such as radar and moving maps, while the right displays system status like engine, landing gear, canopy, flaps, fuel, and weapons. Early F-16A/B models used a single CRT display combined with analog gauges. The MLU upgrade added two night-capable MFDs. Later blocks replaced CRTs with LCDs, and Block 60 introduced programmable color MFDs with picture-in-picture and real-time moving maps.

Avionics include precise navigation via the Embedded GPS/INS (EGI) system, UHF and VHF radios, and an instrument landing system. Modular warning and countermeasure pods protect against electronic and ground threats. The airframe is designed to allow installation of additional avionics systems.

Lockheed Martin F-16 AM/BM Block 15 eMLU Fighting Falcon armament

Air-to-air radar-guided missile: Raytheon AIM-120C-5/7 Advanced Medium-Range Air-to-Air Missile (AMRAAM) with a range of 105 kilometers.

Air-to-air infrared-guided short-range missile: Diehl IRIS-T (infrared imaging system tail/thrust vector-controlled) AIM-2000 with a range of 25 kilometers.

Air-to-ground infrared imaging missile: Raytheon AGM-65D/G/G-2 Maverick with a range of 22 kilometers.

External fuel tanks

Targeting pod: Lockheed Martin AN/AAQ-33 Sniper Advanced Targeting Pod (Sniper ATP Pod).

Electronic countermeasure pod: Raytheon AN/ALQ-131(V) ECM Pod.

The Thai Air Force’s F-16 AM/BM Block 15 (e)MLU retains the original engine but upgrades avionics, radar (such as APG-68(V)9), and weapons to create a versatile multi-role fighter. The Pratt & Whitney F100 engine remains a crucial element of the improved flight performance.

The Royal Thai Air Force operates F-16s powered by single-engine turbofan engines from two main brands: Pratt & Whitney and General Electric. The Pratt & Whitney F100 variant provides high thrust and supersonic speeds, reaching a maximum speed of 2,120 kilometers per hour—twice the speed of sound (Mach 2).

Key characteristics

Basic airframe structure: Upgraded structure of the older F-16A/B Block 15 airframes.

Engine: Continues to use the single turbofan engine from the Pratt & Whitney F100 family (e.g., F100-PW-220/229), the primary powerplant for enhanced capabilities.

Key characteristics

Basic airframe structure: Upgraded structure of the older F-16A/B Block 15 airframes.

Engine: Continues to use the single turbofan engine, typically Pratt & Whitney F100 series (e.g., F100-PW-220/229), as the main power source for improved performance. The eMLU upgrade includes avionics upgrades equivalent to F-16C/D systems, including:

New AN/APG-68(V)9 radar.

Joint Helmet Mounted Cueing System (JHMCS).

Sniper XR targeting pod.

Modernized cockpit and expanded weapons carriage (AIM-120 AMRAAM, IRIS-T).

Role: Converts older fighters into modern multi-role aircraft capable of Beyond Visual Range (BVR) combat and precise ground strikes.

Engine context

While the eMLU modernizes avionics and weapons, the engine remains a powerful core component. Although newer blocks (such as Block 70/72) may use more advanced engines, the Block 15 eMLU focuses on upgrading the existing airframe capabilities by leveraging the single powerful engine for superior performance.