NASA has released recent images of "A-23A," one of the largest and oldest icebergs in the world, now facing its final stage after turning blue due to rapidly melting ice. It has developed a large crack from the weight of accumulated meltwater, and it is expected to break apart in the South Atlantic Ocean within a few weeks.

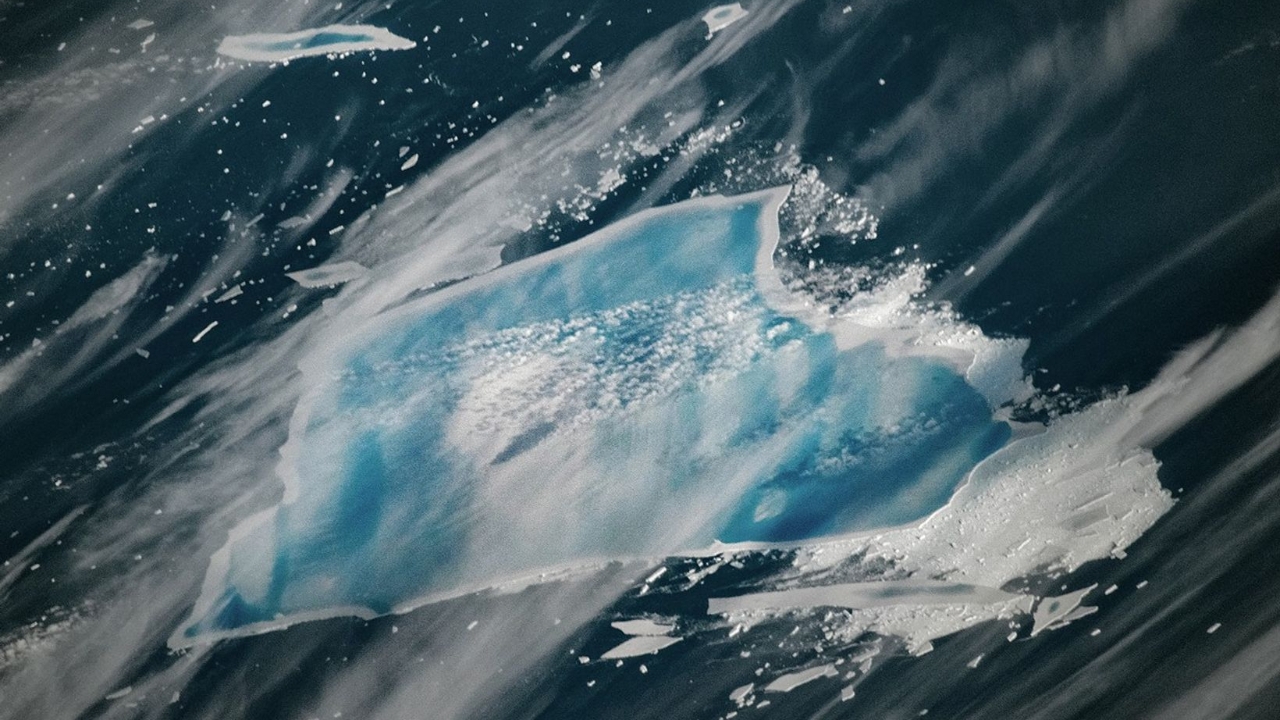

NASA shared satellite photos and images from the International Space Station (ISS), revealing that iceberg A-23A, which once measured 4,000 square kilometers—twice the size of the U.S. state of Rhode Island—is now covered with numerous "blue meltwater pools" on its surface as it drifts near the southern tip of South America.

Experts explain that the enormous weight of the meltwater pools on top of the iceberg has pierced through the ice layer, creating a "crack"—a clear sign that the internal structure is severely weakened.

Currently, A-23A is moving into warmer currents and atmosphere during the Southern Hemisphere's summer, an area scientists refer to as the "iceberg graveyard." Chris Shuman, a scientist from the University of Maryland, predicts that A-23A will not survive this summer and could completely disintegrate within days or weeks.

A-23A has a long and remarkable history. It separated from the Antarctic continent in 1986 with an initial area of 4,000 square kilometers and once hosted a Soviet research station. It remained grounded until 2020 before it began moving northward. In 2025, it nearly collided with a remote penguin colony but fortunately ocean currents shifted direction beforehand.

As of January 2026, its size has shrunk to only 1,182 square kilometers—still larger than New York City but just a fraction of its original size.

Walt Meyer, a senior researcher at the National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC), explained that the blue-white linear patterns seen on the iceberg are grooves worn down over hundreds of years when it was still part of the continental ice sheet. These grooves have become valleys and channels that collect meltwater, accelerating the iceberg's current collapse.

"It's hard to believe it will no longer be with us, but it has been a long journey filled with many events," Shuman said, expressing regret over the loss of a natural resource that humans have observed for nearly half a century.