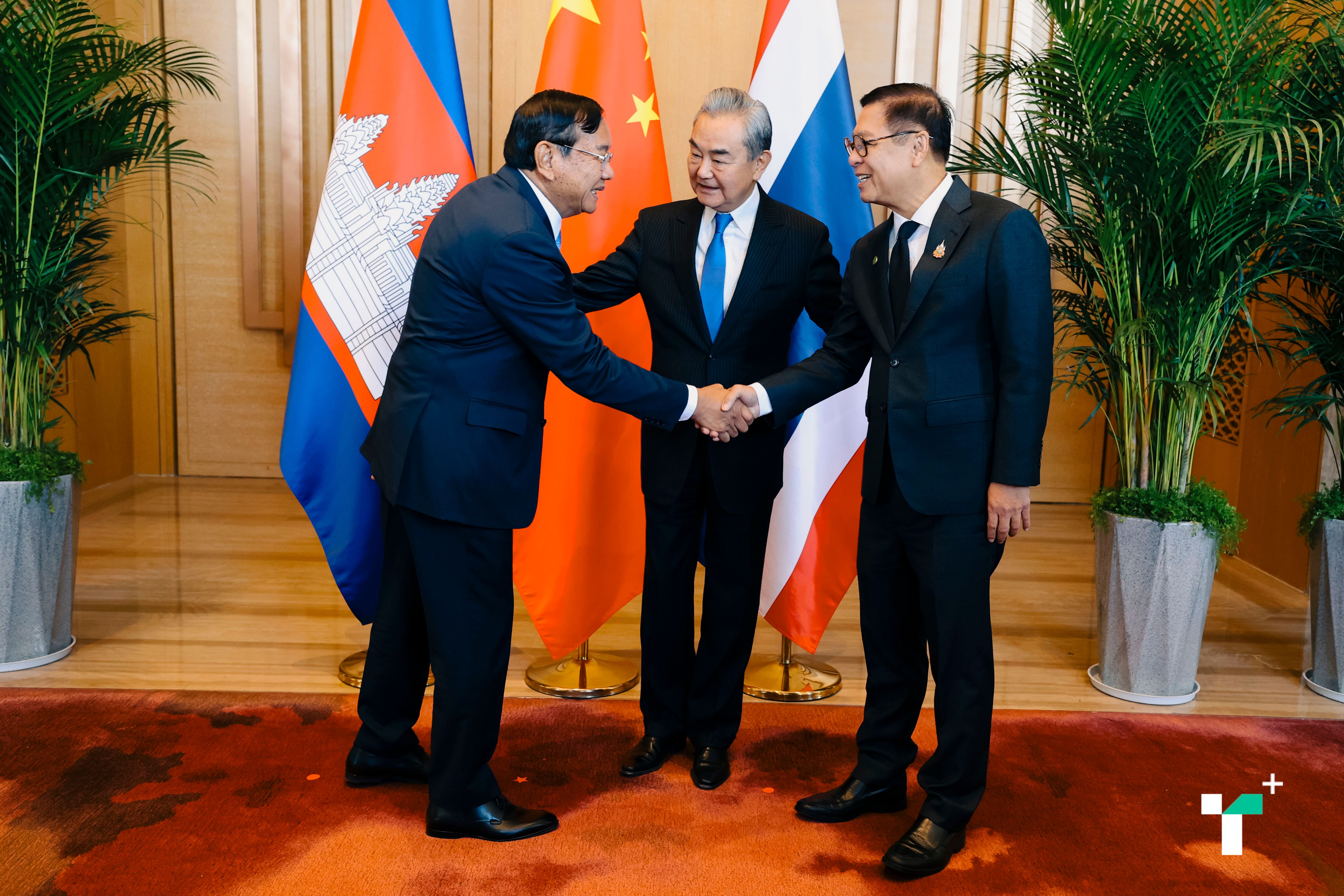

Although the General Border Committee (GBC) meeting between Thailand and Cambodia on 27 December, followed by the tripartite meeting with China in Yunnan Province the next day, succeeded in silencing gunfire and explosions along the border, and displaced persons returned home from war refugee centers, millions living along the Thai-Cambodian border—from Trat-Koh Kong to Ubon Ratchathani-Preah Vihear—remain fearful amid rumors of a third round of clashes.

Scenes of villagers hastily harvesting crops near disputed areas such as Prasat Ta Kwai, Chong Krang, and Prasat Ta Muen Thom reflect not just military tension but a clear policy reality: although fighting has temporarily ceased, the population's insecurity persists. The second wave of clashes, involving artillery and BM-21 rockets striking sugarcane fields, rubber plantations, and residential areas, means that a military ceasefire does not equate to real peace for border communities.

Meanwhile, government and military officials from both neighboring countries continue to propagate narratives of conflict, pride in victory, or mocking of defeat without end. Thailand claims success in 'regaining' what it considers its territory, while Cambodia counters by releasing images and maps showing the actions as an 'invasion' of its land.

All this indicates that the fragile ceasefire rests on mutual suspicion. While positive images are crafted in negotiation rooms portraying this as a sign of eased tensions, voices on the ground among border residents raise a different question: will these ceasefires truly bring safety to the people, or merely postpone the risk of future clashes? This question is central to policy analysis and forms the basis for the following scenarios.

The best-case scenario requires that the ceasefire agreed at the GBC meeting on 27 December 2025 be viewed not as an endpoint but as the beginning of systematic conflict management. Under this scenario, Thailand's civilian government—especially following the 8 February 2026 election—must genuinely oversee border security policy, not just nominally but in practice, reducing military dominance and decision-making roles, while actively involving the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in true diplomatic efforts (not merely justifying military operations as before). The Ministry of Interior and economic-trade ministries must also participate in shaping policy toward Cambodia.

In this scenario, all bilateral mechanisms between Thailand and Cambodia—such as the GBC, Regional Border Committee (RBC), and especially the Joint Boundary Commission (JBC)—must fully resume their roles in surveying and demarcating the land boundary to peacefully resolve foundational issues and prevent border disputes from triggering military conflict.

A crucial factor is that the government and military must recognize the fears of the population as empirical data informing policy, not mere complaints or rumors. Images of villagers in Phanom Dong Rak hastily harvesting crops or rubber tappers in Kantharalak rushing to earn money to prepare for evacuation serve as warnings that the ceasefire is not yet effective in daily life. The government must accelerate proactive communication, reduce rumor spaces, and establish tangible guarantees such as confirmed civilian protection measures, comprehensive, equitable, and adequate reparations, and transparent control of military forces in the area.

In this scenario, the recent Thailand–Cambodia–China tripartite meeting should serve as a political and psychological guarantee mechanism, not a platform for great-power posturing. China’s role should be to support humanitarian and real observation efforts, not to score diplomatic points. Thailand should use this framework to bolster the ceasefire’s credibility rather than to enhance military leverage over its neighbor.

If accomplished, this would yield satisfying results: border residents’ fears gradually diminish, not because of government statements but because state actions align with everyday safety. Harvesting would return to a seasonal activity rather than an escape. Cross-border trade would gradually recover toward pre-mid-2025 levels. This would pave the way for stable cooperation and relationship restoration—not permanent peace, but a significant reduction in the risk of renewed clashes.

The most likely scenario at present is that the 27 December ceasefire remains militarily effective and the tripartite meeting prevents the situation from spiraling out of control, but it will not advance toward peace because the Thai government remains under military influence and continues to view security primarily through a military lens, unable to extend management to build public trust.

In this scenario, border policy remains largely determined by the military. The elected civilian government plays a reactive role, mainly explaining or defending military decisions rather than setting direction. The ceasefire is seen as sufficient, resulting in neglect of communication and rumor management. Mainstream media and influencers will continue to use security and military operations to generate engagement and revenue aggressively.

Consequently, border residents’ fears persist and may become normalized. People cannot conduct normal livelihoods as they remain alert for news of possible new clashes. Media and influencers reinforce the belief that new clashes are always possible. The peace that exists is merely technical, spoken by officials as duty, not felt as real calm by the population.

Optimistically, past and future bilateral or multilateral meetings serve mainly as diplomatic imagery rather than changing behavior on the ground. Minor border incidents risk escalating into larger conflicts easily. Small mistakes, accidents, or rumors of troop reinforcements can push the situation toward the worse scenario at any time.

The worst-case scenario occurs if all mechanisms and factors managing tensions are ignored. The 27 December ceasefire is used merely as a strategy to buy time for the military to rest and rebuild forces. Security power remains firmly in military hands, with civilian government losing any ability to direct security and border policy. Diplomatic mechanisms become paralyzed, and internal tensions justify increased military responses.

In this scenario, public fear is not alleviated but exploited to support hawkish policies. Rumors of troop buildups spread unchecked. Voices calling for peace cannot compete with fears rooted in past experiences. Bilateral and multilateral meetings are viewed more through geopolitical rivalry than peacebuilding, further deepening distrust inside and outside the area.

New clashes are likely, but not from strategic planning; rather from accidents, misunderstandings, or minor localized skirmishes that cripple local control mechanisms. When small incidents escalate, negotiation mechanisms are sidelined. The highest costs fall not on states or militaries but on border residents who must endure cycles of displacement, economic loss, and life in ongoing uncertainty and instability.

In summary, the three scenarios show that Thailand’s internal factors weigh more heavily than Cambodia’s external factors. Phnom Penh’s government has typically proposed peaceful solutions, such as submitting disputed areas including Prasat Ta Muen and Ta Kwai to the International Court of Justice since the May 2025 border dispute. Although Thailand disliked this, it was still a peaceful legal approach. Most recently, after the 27 December ceasefire, Cambodia proposed convening the Joint Boundary Commission to resolve disputed areas.

Conversely, Thailand’s past deference to military control over border security and relations with Cambodia effectively prioritized military solutions over diplomatic ones.

Therefore, from Thailand’s policy options, it is clear who sets the border direction, whether the ceasefire is a conclusion or a beginning, whether public fears are treated as warnings or ignored, and whether international diplomacy is a tool for peace guarantees or just a backdrop for military operations. Past experience suggests that mismanaging these factors risks turning today’s fragile peace into a trigger for renewed conflict.

The key question is not Thailand’s readiness to fight or territorial gains, but whether the state is prepared to manage conflict by centering the lives, security, and welfare of border residents. If policies continue to force villagers to repeatedly prepare to flee, this implies a de facto choice of the worst-case scenario.

Sustainable peace cannot arise from occasional ceasefire declarations alone but requires policy decisions courageous enough to break the cycle of fear before it erupts into gunfire again.

Scenarios. | Phenomena. | Outcomes. |

| Best scenario. |

|

|

| Most likely scenario. |

|

|

| Worst scenario. |

|

|

Source: Compiled by the author.