The Migrant Population Network summarizes the overall situation of migrant workers in 2025, with the registered workforce exceeding 3.6 million. However, management remains ineffective, with fewer than half enrolled in social security. Workers face complex procedures and exploitative brokers charging excessive fees.

On 18 Dec 2025 at the Foreign Correspondents' Club of Thailand (FCCT), Maneeya Building, Bangkok. The Migrant Working Group (MWG), a network of organizations focusing on migrant populations, held a press conference on International Migrants Day 2025 under the theme "2025: From Construction Sites to Battlefields: The Crisis of Migrant Workers from Temporary to Chronic Problems." They also summarized the overall situation of migrant workers in 2025.

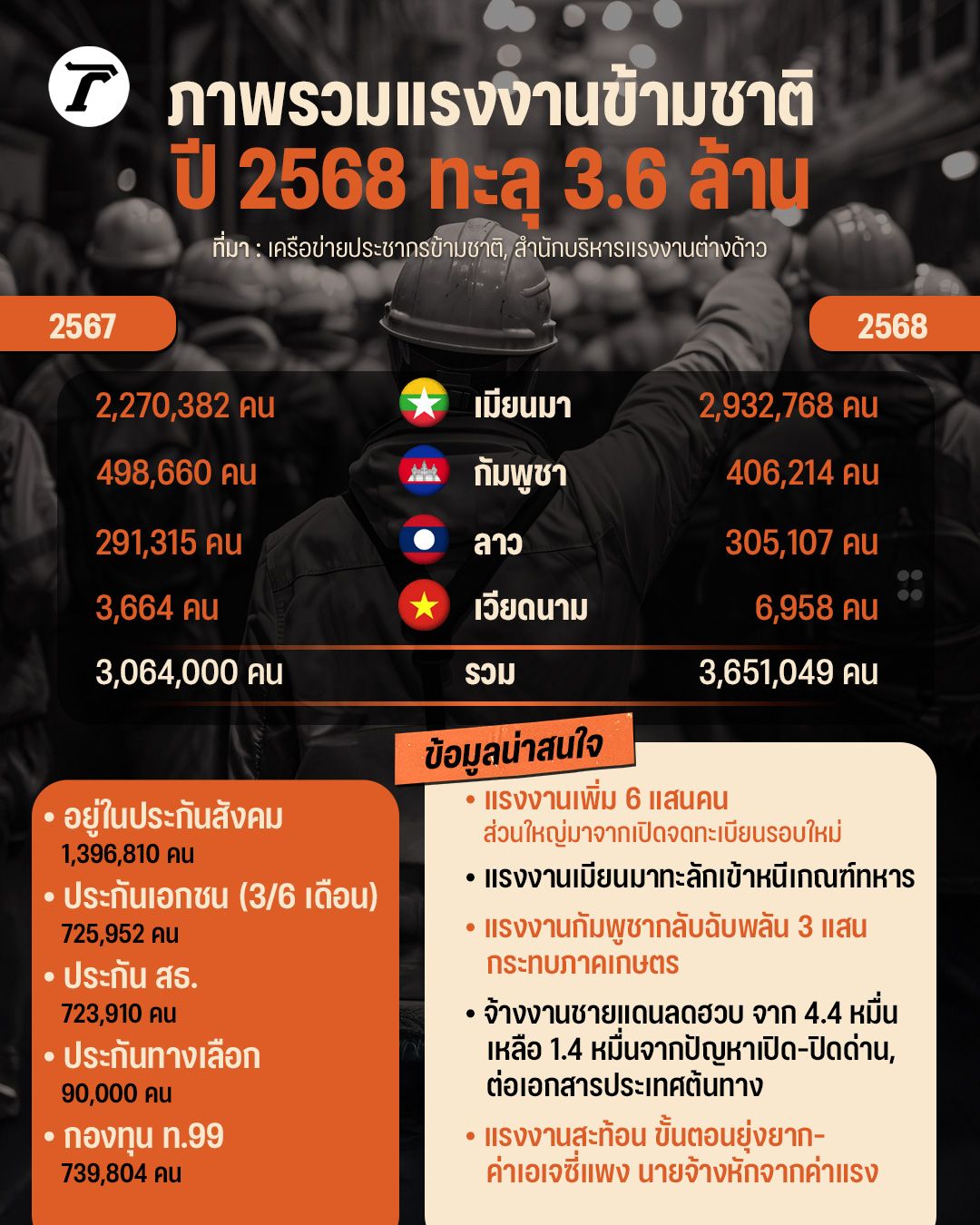

The Migrant Population Network revealed data showing the number of legally registered migrant workers rose from about 3,064,000 in 2024 to 3,651,000 in 2025 (October). The significant increase of over 600,000 mostly comes from a new registration round. Other notable data include:

1. Workers under the MoU scheme legally increased slightly from 635,113 in 2024 to 654,957 in 2025, a rise of about 20,000. This government-designed government-to-government mechanism for legal labor import showed only minimal growth.

2. Border employment declined from 44,771 in 2024 to 14,070 in 2025, mainly due to seasonal workers from Myanmar and Cambodia facing issues with border openings and document renewals in their home countries.

3. Lao workers increased slightly from 291,315 in 2024 to 305,107 in 2025, which is not a significant rise. This counters prior assumptions that Lao workers might replace Cambodian workers returning home.

4. Most Myanmar workers are under Cabinet resolutions allowing temporary status. Although renewal numbers decreased, new registrations have replenished the population, while MoU and seasonal workers declined.

Ms. Roysai Wongsuban, a representative from the Migrant Population Network, revealed that discussions with migrant workers showed most want to stay in the system legally but face complex document procedures requiring approval from their home countries, paying bribes for paperwork often via costly brokers, risking scams by illegal intermediaries.

Ms. Roysai disclosed that migrant workers in the system must enroll in social security. Some awaiting enrollment must undergo health checks and buy private Thai insurance. Those outside social security coverage, like domestic workers, maids, and caregivers, must purchase Ministry of Public Health insurance. Others buy private alternative insurance from 20 providers, and some join the T.99 fund for those with status or rights issues (awaiting Thai nationality verification). The breakdown is as follows:

- Workers in the social security system: 1,396,810 people.

- Self-paying private insurance (3 or 6 months): 725,952 people.

- Ministry of Public Health insurance purchasers: 723,910 people.

- Alternative private insurance buyers: 90,000 people.

- T.99 fund members: 739,804 people.

Comparing these figures shows only about 1.4 million migrant workers are in social security, less than half of the total 3.6 million in Thailand. The resulting gaps burden the public health system, causing some Thais to worry these workers may be a threat or compete for resources.

Moreover, even workers in social security face difficulties accessing medical benefits and compensation because employment documents between workers, actual employers, and brokers often do not match. This happened in cases of death or disability from the collapsed S.T.O. building and for workers affected by recent flooding-related work stoppages in Hat Yai.

Mrs. Nilubon Pongpayom, representing the White Employer Group, revealed concerns about private insurance, including accusations of collusion. Some insurers contract with hospitals not accredited by the government. When workers fall ill, state hospitals provide care under human rights principles, adding costs to Thailand's public health system. Additionally, private health insurance shouldn't exceed 3 months, but a Ministry of Labor announcement (Cabinet resolution) allowed workers to buy up to 6 months coverage while processing work permits, creating a loophole enabling avoidance of social security enrollment.

Ms. Roysai explained that Cambodia's labor situation in Thailand is affected by sudden worker repatriation due to border conflicts and inability to renew documents, as the Cabinet has yet to approve extensions for documents expiring in March 2026. Some workers continue working while waiting, but many have already returned.

Additionally, seasonal or non-daily border workers disappear automatically when border crossings close. It is estimated over 300,000 workers have returned, possibly more.

Cambodian workers concentrate in certain industries, especially agriculture, which has been severely impacted in crops like longan, sugarcane, and durian with limited harvest windows. Though considered unskilled, these workers have expertise in fruit care and harvesting, not easily replaced. Kasikorn Bank research estimated the Cambodian labor crisis caused damages of about 2.6 billion baht to the longan business. Thailand is now entering the sugarcane crushing season, expected to be similarly affected.

Worryingly, it's unclear when Cambodian labor will recover due to lingering animosity from the conflict, which may take years to fade. Cambodian worker numbers may decline, possibly replaced by other labor groups, but replacement is uncertain. For example, importing Sri Lankan workers involves higher travel costs, social and cultural differences, and if higher-paying countries like Malaysia attract them, they may not choose Thailand.

“We believe citizens of both countries do not want war escalation. Although many see conflict as unavoidable, both sides understand prolonged conflict damages economies and societies, including trade and employment. Some Cambodian workers said upon return, jobs are scarce or pay much less than in Thailand, insufficient for expenses. In other words, Thai employers need workers, and workers need income; they depend on each other.”

Many employers, especially in agriculture, are small operators without deep financial reserves. Labor shortages impact business operations and income, with some hesitant to invest next year due to labor market uncertainty.

“It is unfortunate because we have opportunities to develop the economy and society, creating mutual benefits as neighbors, enhancing regional stability in investment and tourism, but hatred divides us.”

Mr. Adisorn Kerdmongkol, a representative of the Migrant Population Network, said that in 2025, Thailand saw three different Labor Ministers who lacked expertise or understanding of labor issues, focusing on short-term problem management. This year, Thailand faced crises managing migrant workers due to internal political problems in Myanmar, including military conscription pushing laborers to flee illegally into Thailand, and Cambodian border conflicts causing mass repatriations.

Previously, migrant worker renewals were handled solely by Thailand, raising questions about why home countries had to be involved despite unfavorable conditions. When delays occurred in home countries, the Cabinet issued resolutions extending work permit renewals and temporarily allowing work, solving immediate problems but not systemic labor issues.

Ms. Roysai revealed that in 2025 the government allowed refugees to work to address labor shortages and generate income, estimating 40,000 working-age refugees. Though a policy advance, practical obstacles remain. Only a few thousand have been processed because the method does not align with labor market realities. Employers must recruit directly in refugee camps, which is difficult, and small employers lack resources to do so. Documentation procedures are complex, and workers may lack desired skills.

Labor issues are critical for government attention because international trade negotiations, especially with Western countries like the U.S., annually report on child labor, forced labor, human trafficking rankings, and the EU, with which Thailand is pushing FTAs, prioritizes labor welfare.

For example, a joint statement signed by Thailand and the U.S. at the ASEAN meeting in October 2025 pledged to protect labor rights. Although this statement is currently stalled, it reflects labor's importance in international trade talks.

Mr. Adisorn pointed out another challenge: the Department of Employment launched an online system, E-workpermit.doe.go.th, for work permit applications and related migrant labor procedures, outsourcing work permit production and application services since 13 Oct 2025.

However, problems with system access and processing work permit applications have affected employers, migrant workers, and recruitment companies, hindering operations. This may severely impact migrant labor hiring. The Department's problem resolution has been slow, leaving over one million Myanmar migrant workers—including those needing permit renewals by 13 Dec 2025, skilled workers, and MoU workers—at risk of becoming undocumented.

“Problems include employers and employees being unable to find their information because past registrations occurred in multiple rounds with changing systems, causing data loss. The system needs improvements focusing on actual users. Developing the e-WorkPermit system will bring long-term benefits, enhancing convenience and reducing corruption.”

Ma Oo, a 58-year-old Myanmar migrant with over 25 years in Thailand, said conditions have improved since she first arrived as the government promotes legal registration. However, complex procedures now require more documents, including a specific passport and identity certification, making access difficult and pushing workers out of the system.

Due to these complex steps, employers use costly agencies to handle visa renewals and deduct fees from workers. Some factories’ HR departments charge workers bribes. Many workers cannot afford expenses, resort to debt, and by visa renewal time, debt remains. Consequently, many quit and work illegally, exiting the system. Additionally, since Myanmar's coup, the military government imposed a monthly 150 baht tax.

“Renewing a visa independently costs under 4,000 baht per person, but agency fees can reach tens of thousands, making it unaffordable. Previously, there was no tax. Now, the military government demands back taxes for passport renewals, document requests, and without payment, documents are withheld.”

Ae, a Myanmar worker network representative from Chonburi, hopes the government can simplify procedures or allow employers to authorize migrant workers to handle paperwork themselves since currently authorization is limited to Thai nationals, forcing employers to use agencies.

Ms. Roysai also urged the next government to first acknowledge Thailand’s changing demographic structure and the need for labor—both Thai and foreign—to drive the economy. Secondly, given Thailand’s heavy reliance on labor in production, reducing dependency requires greater investment in technology and innovation. The government should support businesses in transitioning to higher value-added production technologies. But if labor reliance continues, the state must be open to addressing labor issues systematically.