Myanmar workers in Thailand openly reject the election, with only a few hundred voting, calling it a theatrical performance to legitimize the military government. Scholars see it worsening internal problems and driving a surge of migrants into Thailand.

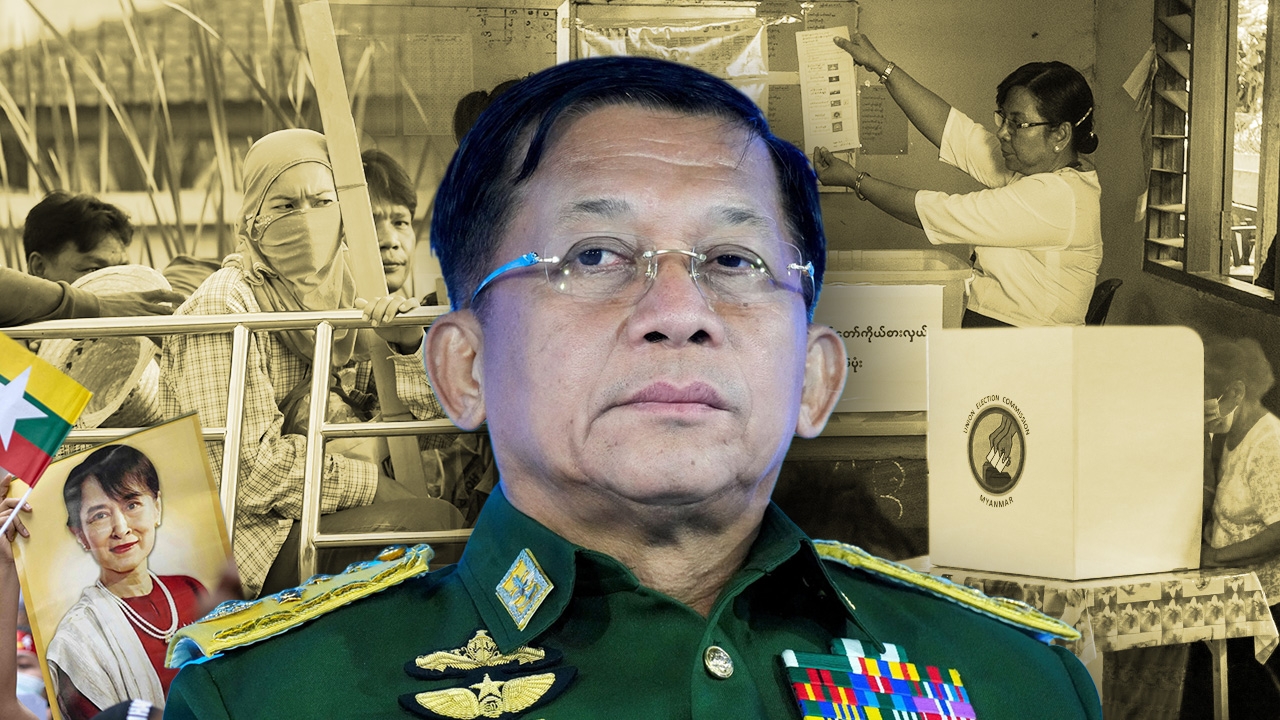

While Thailand is advancing towards its general election in 2026, with political parties announcing candidates and campaigning, the neighboring country, Myanmar, is also preparing for elections starting 28 Dec. This marks the first election since the military coup in 2021.

Amid rumors about the death of former leader Aung San Suu Kyi, and widespread criticism that this election is a Sham Election, or a farcical election, which is neither free nor fair but merely an attempt to legitimize the military government. Over 200 Myanmar citizens who protested or criticized the election have been prosecuted for obstructing the vote.

Myanmar’s parliamentary structure follows the 2008 constitution, which maintains strong military influence. It consists of

The upcoming Myanmar election in 2025 is divided into three phases, and will not be held nationwide due to ongoing civil conflict and the military’s inability to control all territories. Voting will occur on 28 Dec 2025, 11 Jan, and 25 Jan 2026, covering approximately 145 constituencies out of 330 under military control.

Nearly 60 political parties have registered candidates, mostly small parties or those aligned with the military. Among these, six parties are contesting nationwide, along with 29 ethnic parties.

The six nationwide parties are: the Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP), seen as the military’s proxy party, including many former senior military officers and ministers from Min Aung Hlaing’s government, who have filed candidacies and are expected to win the election. The others are the People’s Party led by U Ko Ko Gyi; the People’s Pioneer Party led by Daw Tet Tet Khine; the Shan and Nationalities Democratic Party led by Sai Ai Pau; the Arakan Front Party led by Dr. A Hmong; and the Kachin State People’s Party led by Dr. Tu Ja.

These are not new parties but have historically lacked popularity and maintain close ties to the military regime. Meanwhile,

the National League for Democracy (NLD), led by Aung San Suu Kyi and formerly the ruling party, was dissolved in 2023 after refusing to register under the military’s new political party law. Voices from Myanmar Workers in Thailand According to 2025 migrant labor data,

Thus, Myanmar’s election outcome and internal situation inevitably affect Thailand, as seen recently with an influx of war refugees and migrant workers fleeing forced conscription policies by the military government. Thairath Online’s special team spoke with A, a Myanmar worker in Chonburi province,

who revealed that Myanmar workers in Thailand show almost no excitement about the upcoming election.

There is little interest, including from himself, viewing the election as non-transparent. He estimates less than 5% of Myanmar workers will vote, mostly family, close associates, or supporters of the military party. “We don’t vote because we know it’s pointless. Even if we do, the military government will win anyway. Also, the election isn’t fair, and the party we support is no longer participating. The existing parties don’t seem very effective,” he said. Comparing to the 2020 election, the atmosphere now is entirely different. A recalled that in 2020, Myanmar workers from all over Thailand took buses to vote at the Myanmar embassy, crowding Sathorn Road. “In 2020, Sathorn Road, where the embassy is located, was packed with workers, almost impossible to walk. Workers came from far places like Hat Yai, Pattani, and Ranong by bus. Even from Chonburi, I returned home around 2 a.m. But this time, hardly anyone in Chonburi plans to vote.” A believes that after the election, the military will continue to govern and remain indifferent to Myanmar workers’ welfare in Thailand, possibly worsening conditions.

He noted that during the past five years, tax collection measures have been imposed, and after legitimizing through the election, tighter regulations restricting rights and freedoms may follow.

Election Drives More Migration to Thailand

Dr. Sirada Khemanittha Thai from the Faculty of Political Science and Public Administration, Chiang Mai University,

explained that the Myanmar election is not truly nationwide. The country is divided into 330 townships, small towns or subdistricts, with over 50 townships excluded from voting.

The inability to hold elections everywhere is due to intense ongoing fighting, even in areas not controlled by ethnic armed groups, such as Sagaing Region, a central area mainly inhabited by the Bamar majority who strongly oppose the military government. Since the election announcement, conflict has escalated rather than diminished. Dr. Sirada believes the election and intensified fighting may cause increased irregular migration of Myanmar people into Thailand—migrating without proper documentation to avoid dealing with the government. Those already in Thailand may avoid returning, resulting in many falling outside official systems, posing management challenges for the Thai government. “An election organized by the military government won’t alleviate the migration crisis from Myanmar to Thailand because it’s neither free nor fair, nor will it lead to real reforms. Instead, it will concentrate more power, and the impacts on Thailand from Myanmar will persist and increase.” Data show that since the 2021 military coup, migration motivations have become mixed—people flee not only for economic reasons but also to escape war and seek livelihoods.

Additionally, forced conscription by both the military government and armed groups has driven many young Myanmar men and women to flee into Thailand. After legitimizing itself through elections, the military government is expected to tighten migrant labor controls both at origin and destination.

Early voting in Thailand occurred from 6-7 Dec in Bangkok and Chiang Mai, with only a few hundred voters despite an estimated Myanmar population in Thailand of up to 4 million, clearly indicating widespread rejection of this election.

Beyond domestic politics, there are geopolitical concerns including China’s involvement in resource extraction, and Russia and Belarus’s roles in large development projects such as special economic zones and nuclear power plants, potentially causing other types of displacement among Myanmar people.

Source: Parts of this report are from the seminar “Opportunities for Thailand through Comprehensive Migrant Labor Management Strategy,”

parliament.go.th,

rfa.org,

britannica,