Currently, technologies for electricity generation are continuously developed to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, particularly electricity derived from clean energy sources. For example, solar cells that generate power from sunlight or turbines that produce electricity from wind energy.

Thailand has approved building a new natural gas power plant in Chachoengsao Province, contradicting the Net Zero 2050 target.

Recently, Thailand announced its official plan to achieve net zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050. This was declared at the COP30 meeting on 19 Nov 2025 GMT+7, with an additional target to reduce emissions by 47% by 2035.

Whether these goals will be achieved partly depends on the National Energy Plan (NEP). The NEP is the master plan guiding national energy policy development, managed by the Energy Policy and Planning Office (EPPO) under the Ministry of Energy. It includes five other plans:

1. Power Development Plan (PDP), overseen by EPPO.

2. Natural Gas Management Plan (Gas Plan), also overseen by EPPO.

3. Energy Conservation Plan (EEP), managed by the Department of Alternative Energy Development and Efficiency (DEDE).

4. Alternative Energy Development Plan (AEDP), also managed by DEDE.

5. Oil Fuel Management Plan (Oil Plan), managed by the Department of Energy Business.

One of the most debated plans in society is undoubtedly the PDP. The PDP directly affects every electricity consumer because it is the master plan for investment in Thailand's power system, forecasting national electricity demand to plan generation investments 15-20 years ahead.

Currently, the new PDP draft aiming to increase clean energy use and reduce fossil fuel dependence was canceled before completion.

Due to delays and political changes, the new PDP draft will only progress after the 2026 election, so Thailand continues following the longstanding 2018 PDP first revision—the longest-used PDP to date.

A key issue is that the 2018 PDP first revision still prioritizes electricity generation from fossil fuels, clearly illustrated by a binding contract to build a new natural gas power plant in Chachoengsao Province, which has been contracted but not yet constructed due to ongoing local opposition caused by concerns over environmental, water, and lifestyle impacts.

However, in late October 2025, the Energy Regulatory Commission (ERC) granted a license to a private company, meaning the natural gas plant has been approved for construction and will start supplying power under contract by 2027.

This outcome, amid local opposition and Thailand's transition to Net Zero, raises many questions about the necessity of building fossil fuel plants, especially given credible data showing electricity capacity in the Eastern region is already sufficient.

Additionally, local residents already facing pollution, water shortages, and agricultural impacts from existing power plants and factories may confront increased burdens from new developments.

All this prompts a renewed question: how can Thailand transition to clean energy and promote sustainable economic development?

"We must fight because we understand the impacts. Since 1999, two biomass power plants were built here, and their effects are clear—starting with water issues due to water use and wastewater discharge, which seeped and contaminated shallow wells, making them unusable, alongside dust and other pollution," said Kanjan Tattiyakul of the Chachoengsao Repower Network, explaining the origins of opposition.

Kanjan said the planned additional power plant initially began as the Khao Hin Son coal-fired plant. Its Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) was approved, but under the 2007 constitution, coal plants are classified as high-impact projects requiring an Environmental and Health Impact Assessment (EHIA). Thus, the original EIA was invalidated, and a new EHIA process had to start.

Kanjan described that the EHIA process began in 2011 and continued until 2017, with four submissions all rejected. The project then went quiet until 2019, when it switched from coal to imported LNG gas fuel.

"This time, no matter what data we presented, unlike with the coal plant, the gas plant's EIA passed approval quickly in January 2021, during the difficult COVID-19 period for us," he said.

"After EHIA approval, we actively protested in 2021 since the project stalled during COVID, but later we learned that local residents received notices about land rights being reserved for high-voltage power line construction to the project, signaling progress."

Kanjan explained that in 2025, locals formally opposed the project early in the year. The ERC coordinated with residents, promising to visit the area on 22 Oct to gather comprehensive information before deciding on the license. However, the ERC scheduled the license review for 15 Oct, before the site visit.

"Thailand currently has excess electricity capacity, which burdens electricity costs. Continued reliance on fossil fuels at high proportions will hinder global green competitiveness and worsen climate change impacts. These factors demand a just energy transition to mitigate the climate crisis," Kanjan stated.

Beyond fossil fuel concerns, establishing more factories increases resource demand, with water being a critical issue since natural freshwater cannot be replenished locally, making allocation a key problem.

Kanjan noted that the Tha Lat canal in Chachoengsao supplies raw water for municipal water production, but in 2019, due to low rainfall, the waterworks reported an inability to supply water as there was none to pump.

"According to irrigation principles, water allocation priority is first for consumption, meaning village and regional water supply systems must receive water first if scarce; second is ecological systems; third is agriculture; and last is industry. However, in reality, this priority is not maintained."

Phra Athon Panyapatipo, abbot of Wat Tha Mai Daeng in Chachoengsao Province, who was born locally and has ordained for over 17 years, reflected that in 2017, shallow wells used by villagers were found contaminated due to industrial expansion. Authorities then posted signs prohibiting shallow well use, forcing villagers to buy water. The temple now buys about 10,000 packs monthly. During dry seasons, the municipality supplies external water stored in tanks for 2-3 months annually.

"The waterworks uses drinking water from the Department of Industrial Works, sourced from Rabaem canal. The reservoir, about 300-400 rai, is insufficient year-round and dries up in dry seasons. If factories expand, locals and I worry about water shortages," said Phra Athon.

Electricity generation requires infrastructure like high-voltage power lines. In large agricultural areas like Chachoengsao, power line construction is akin to roadside poles and trees often being cut down entirely because they interfere with power lines and pose hazards.

"They never informed us that they would take our land. They never asked the villagers. They just came and took it," said Supranee Srisawat, a local resident of Chachoengsao Province.

"It's been nearly three years since we first learned about the power lines affecting us. We have continuously petitioned from the subdistrict administrative organization, district office, provincial Ombudsman, deputy governor, up to the Ministry of Energy, but still have no answers."

Meanwhile, Saichon Chuen-arom, a 57-year-old local also impacted by the power lines, explained that the power poles require a 60-meter clearance (30 meters on each side), resulting in loss of land used to grow valuable palm and perennial trees.

"My income from the whole plot mainly comes from palms, earning tens of thousands monthly—up to 50,000-60,000 baht. The forest trees currently do not generate income as they are perennials, but if kept for 10-100 years, their value would be tremendous."

Saichon said electricity officials counted trees and marked them in red to calculate compensation but could not specify amounts yet.

"But we don't want money; we want nature," Saichon emphasized and added, "We have filed an administrative lawsuit, but progress is slow despite years of effort."

Meanwhile, Wisakha Srikasem, a 60-year-old landowner, tearfully said, "We want to keep land for our children to farm," fearing loss of ancestral farmland.

Wisakha said her orchard grows Takian and palm trees since her parents’ time. Normally, palms are harvested every 3 years, yielding 20,000 baht per rai per harvest, but now only short trees up to 3 meters can be planted, limiting crop variety.

Chachoengsao is a key province producing and exporting food nationally and internationally, especially mangoes—a vital economic crop. However, industrial development has forced many mango farmers to abandon hundreds of rai of orchards.

Currently, Chachoengsao hosts over 30 power plants, serves as a central hub for natural gas pipelines to central and western regions, and is a clean energy production base supporting the RE100 (100% renewable energy) policy of multinational companies in the EEC area.

With so many responsibilities, developing the area with regard to local conditions and community lifestyles is crucial for sustainable economy and quality of life.

Nantawan Handee, a power plant impact monitoring network member and part of an organic farming group in Chachoengsao, explained the impacts, noting that no government or academic studies have yet assessed the overall agricultural effects of large projects.

Nantawan said Chachoengsao's special feature is its mix of brackish, fresh, and saltwater, resulting in exceptionally high biodiversity of plants, herbs, and organisms rare in Thailand.

Close to Bangkok, Chachoengsao has long been a food production hub, notably the country's largest mango producer and a top exporter, especially famous for Nam Dok Mai mangoes. It also raises freshwater and saltwater aquatic animals, livestock, and eggs.

"We believe food security is the most critical issue, especially linked to the worsening climate crisis. Thailand’s most vulnerable challenges are food security and water cleanliness. Development must prioritize these over industry or electricity production,"

she said.

"Regarding mango farmers, it's not only about land but also the quality of mango cultivation knowledge and traditions. Losing Chachoengsao mangoes means losing superior quality mangoes. The new power plant in Chachoengsao has no measures to mitigate agricultural impacts."

Nantawan observed that affected people often must defend their rights alone, while government agencies and existing laws fail to protect them or provide easy access to information.

"Regarding fairness in participation in decisions on large-impact projects affecting us and society, these issues are not communicated to the public. Instead, communities must fight alone, while energy projects are portrayed as national public benefits, complicating efforts to have our voices heard," Nantawan said.

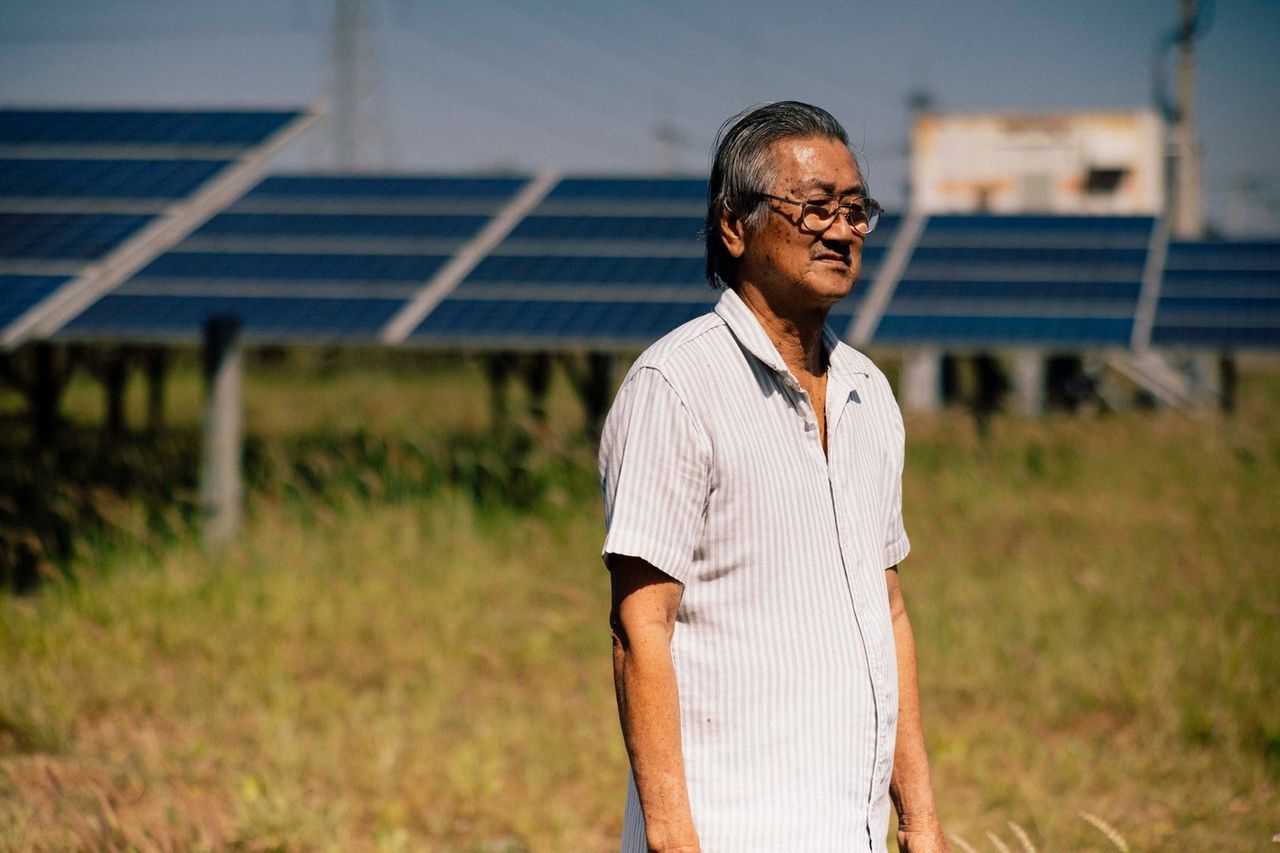

Agricultural impacts are major neglected problems as large industrial projects receive more attention. Many farmers must adapt to survive, revealing clear lifestyle changes. In Khao Hin Son subdistrict, Phanom Sarakham district, a solar power plant stands where mango orchards once were, including land owned by Khun Prommanee,

who rents land for the solar farm.

"My total land is about 200 rai; some still have mangoes, but I want to quit. It's very difficult; mango trees are declining, and younger generations don't farm mangoes anymore,"

Legal process perspectives Supaporn Malailoy, manager of the Environmental Law Foundation (EnLAW), explained that a key legal issue is limited public access to electricity purchase agreements, which are important but often withheld despite requests.

Supaporn said sellers hold contracts, but these are not binding without licenses. Developers must follow legal procedures requiring three permits from the ERC before construction or power generation:

1. Building construction permit, which involves local authorities. After ERC receives a building permit request, it forwards details to local bodies (subdistrict or municipality) to check zoning or legal compliance. Locals review and send opinions back to the ERC for approval decisions.

2. Factory operation permit, requested after building permits, where ERC forwards documents to the provincial industry office to verify factory establishment laws. The Factory Act requires public hearings, but these legally only involve posting announcements for 15 days for objections, after which feedback is summarized for the ERC's approval decision.

3. Energy operation permit, which reviews documents under regulations. Since fossil fuel plants in Chachoengsao require an EIA, public hearings mainly occur during the EIA process, not within ERC procedures.

Supaporn explained that during the EIA process, the project owner hires a consulting firm registered with the Office of Natural Resources and Environmental Policy and Planning (ONEP) to prepare the EIA report for submission to ONEP, including defining scope and holding two public hearings.

The first hearing defines the scope with stakeholders, informing them when and how public input will be gathered. Guidelines require assessing impacts on at least a 5-kilometer radius; if impacts extend beyond, wider consultation is needed. However, usually only 5 km is assessed, and larger impacts, like high-voltage power lines, are often excluded.

The second hearing occurs after impact assessment and mitigation planning, presenting the assessment report and mitigation measures to stakeholders again. Regulations require at least two hearings, often exactly two.

"When the report reaches ONEP, it is reviewed by expert committees to verify accuracy. If inadequate, it's sent back for revision. This process treats the EIA like a thesis checking completeness rather than assessing real local impacts,"

Supaporn said, adding, "This long-standing system problem lacks genuine opportunities for stakeholders and local residents to participate."

Although local opinions generally support sustainable economic development and environmental protection, their voices are not heard in decision-making processes. This reflects deep-rooted problems continuously damaging the environment and community livelihoods with no sign of resolution.