The eastern election battleground features a fierce clash between "bullets" and "momentum" as candidates compete intensely for seats. A former Chonburi politician views this as a key area where political parties hope to seize votes from the "Orange Party" to help form the government.

As the 2026 general election enters its final phase, political parties and groups are intensively campaigning to gain votes, including through visits, speeches, debates, and policy presentations.

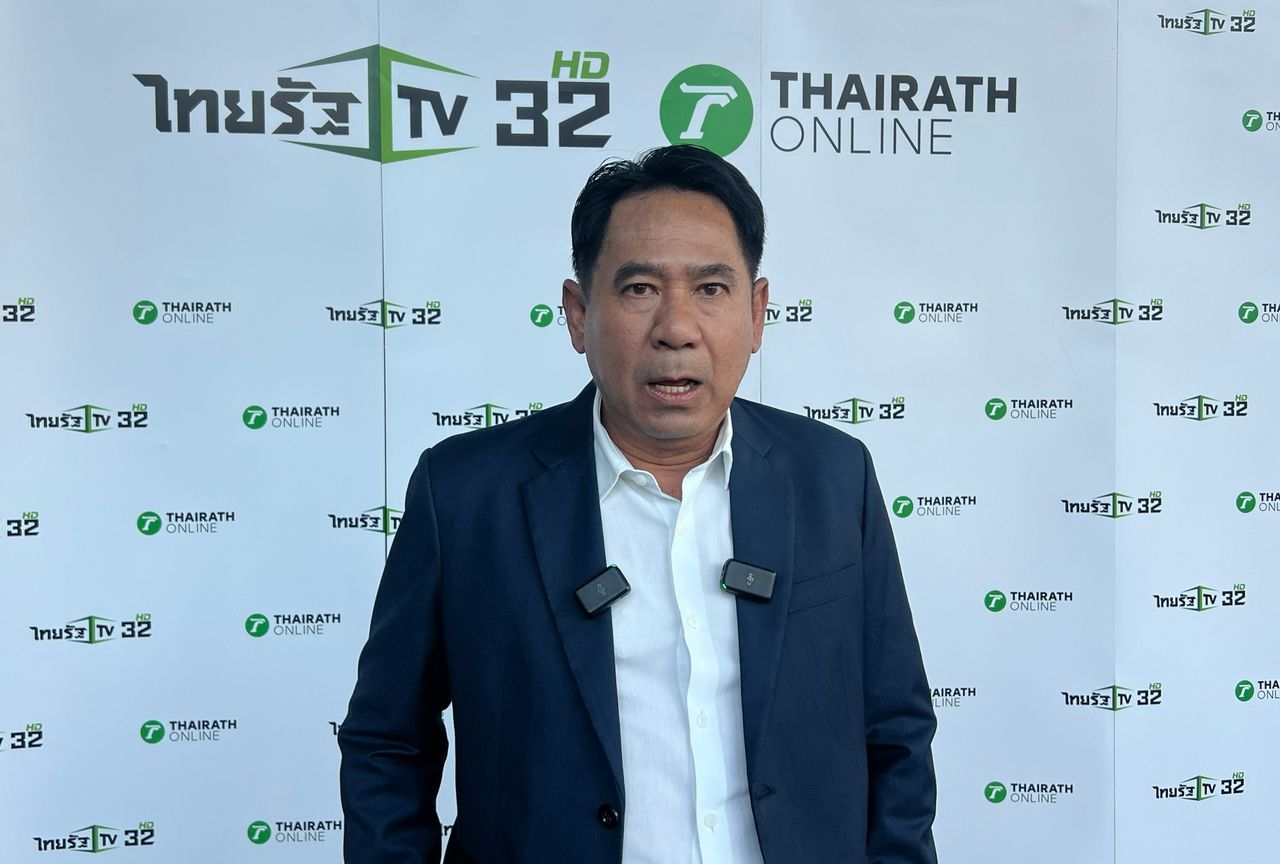

Thairath Online news team Interview with Mr. Sakda Nopasit, a former local politician, from Chonburi province, on the overall election outlook in the “Eastern region.” This is another fiercely competitive area where vote tallies can shift at any time.

Mr. Sakda assesses that the Eastern region sees high competition and strong public interest, especially in Chonburi province, which has 10 parliamentary seats—among the top in the country. Including other eastern provinces, the 2023 election results showed the former Move Forward Party securing 17 out of 29 seats. Therefore, political parties aim to wrest seats from the People’s Party to become number one and form the government.

Mr. Sakda believes that beyond policy issues, the contest is now between the “momentum” of the candidates and “bullets,” meaning vote-buying that still occurs in some areas.

“No matter how strong the momentum is, if bullets are used to induce people to vote, the popularity can change.”

Mr. Sakda identifies three key factors enabling momentum to sustain despite pressure from bullets:

1. A youth and young voter base,

2. Educated voter groups,

3. Groups with stable economic backgrounds.

He sees “bullets” as influencing undecided voters, especially those accustomed to vote-buying. With the current poor economic situation, bullets may regain influence over voter decisions.

Regarding reports of vote-buying at 7,500 baht per person, Mr. Sakda believes the 3,000-7,500 baht figures likely relate more to local elections, where the target population is smaller and only a few thousand voters must be paid, unlike large elections such as for MPs. Some politicians calculate target votes before setting campaign budgets.

Mr. Sakda emphasizes that vote-buying reflects improper political intent. Those who buy votes do not aim to serve in parliament but seek power for personal gain. With a 4-year MP salary totaling about 4.5 million baht, spending 50-60 million baht to buy votes suggests a plan to recoup the investment.

Moreover, vote-buying is illegal for both buyers and sellers. He advises voters who are approached with requests for names to refuse or avoid accepting money. Even if names and ID numbers are given, on election day vote brokers may call to follow up, but they cannot verify how individuals actually voted, only the counts at polling stations.

“If someone tries to buy your vote, you shouldn’t sell it. But if you can’t avoid it, no matter whom you vote for, the brokers will never know. Don’t believe claims that they can verify your vote.”

Mr. Sakda reiterates that vote-buying is wrong. Holding MP elections every four years allows candidates to present themselves to serve the people, express ideas, and campaign to gain support. Today, if voters think a candidate is good and suitable, they should vote for them. If they voted before and the candidate performed poorly, they can change their choice. He urges voters to exercise their rights honestly, choosing representatives who prioritize the people's and country's interests.