Revealing three government sector scams: “embezzlement of public funds,” “extortion and bribery,” and “internal exploitation.” This corruption cycle highlights systemic failures that erode budgets, public trust, and the nation's future.

The Anti-Corruption Organization (Thailand) stated that corruption funds have long been a chronic problem eroding Thailand’s economic and social structures. The current system still allows corruption to persist continuously—from budget processes and law enforcement to power relations among the state, private sector, and citizens. In many cases, these irregularities have been overlooked, normalized, and left unaddressed.

When corruption becomes part of the structure, the problem goes beyond punishing individual offenders. It requires examining oversight mechanisms, transparency, and accountability of those in power, as well as addressing the critical public questions: “How should this problem be solved?” and “Who should truly be responsible?” Systematically exposing corruption forms and methods may be a crucial step toward revealing the full scope of issues hidden behind national governance.

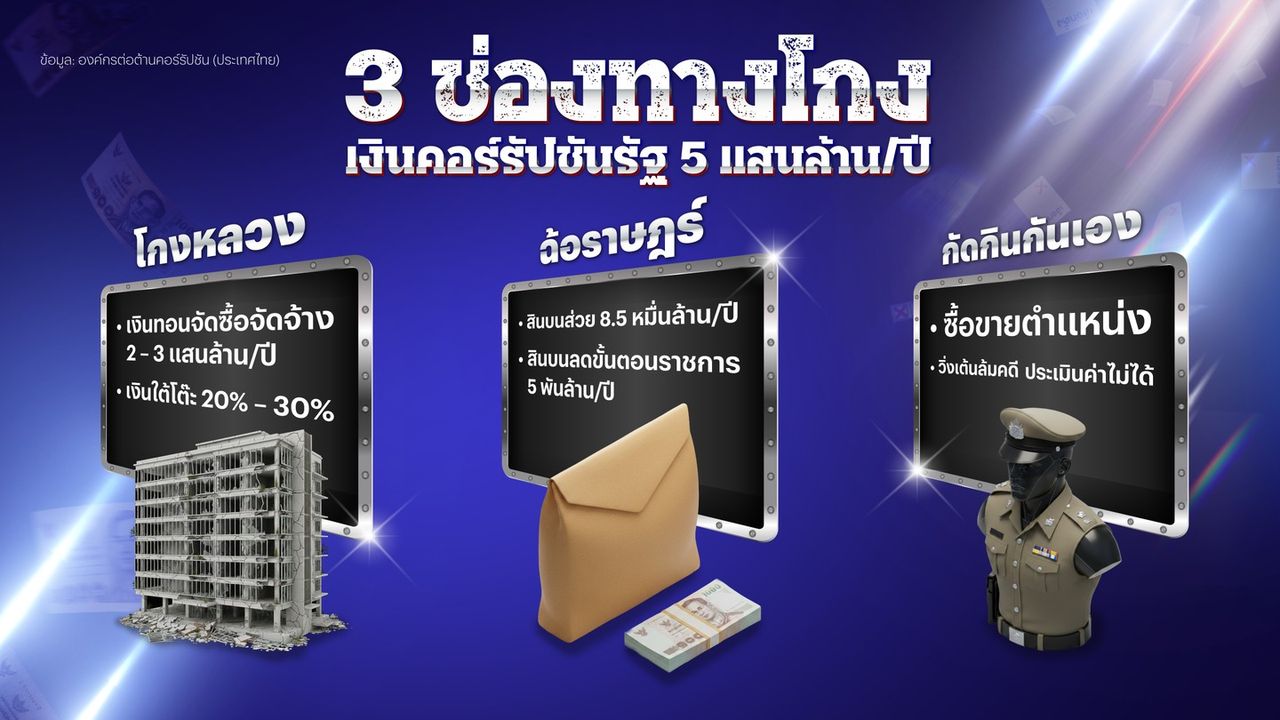

A survey report by the University of the Thai Chamber of Commerce’s Thai Corruption Situation Index reveals that corruption in the public sector amounts to about 500 billion baht annually, stemming from three main scam types:

1. Embezzlement of Public Funds

Corruption in public procurement causes severe damage, with “kickbacks” estimated at 200–300 billion baht per year, or about 20–30% of investment and procurement budgets. Additionally, the state is exploited to favor private interests, such as excessive subsidies for PPP projects, inappropriate concession extensions, infrastructure investments benefiting certain private parties, purchasing overpriced and surplus electricity, under-collecting royalties from mining concessions, and leasing state assets at undervalued rates. Direct embezzlement of state funds also occurs, including park entrance fees, subsidies, and various funds, with cases ranging from minor amounts to losses reaching hundreds of millions of baht. These issues reflect structural problems in governance and public sector oversight.

2. Extortion and Bribery

Beyond bureaucratic corruption, there are issues of bribes and protection money linked to the informal economy, including illegal lottery, gambling dens, drugs, and undocumented labor, valued at about 8–13% of GDP or roughly 1.7 trillion baht annually. Assuming a 5% protection fee, payments could total 85 billion baht per year. Ordinary citizens also pay household-level bribes for various administrative services, amounting to no less than 5 billion baht annually. Business sectors pay bribes for survival or advantage, licenses, and invisible, undetectable payments outside official premises. Altogether, these bribes exceed 100 billion baht per year, with the most affected being low-income citizens and those committed to integrity.

3. Internal Exploitation

Corruption within government officials—such as buying and selling positions, paying to influence case dismissals, and distributing protection money along hierarchical lines—is frequently encountered. Although individual case amounts may be smaller, this structural problem is severe because it perpetuates a bureaucratic system revolving around patronage and illicit revenue generation, especially in agencies with high stakes. Meanwhile, the state spends substantial budgets combating corruption; in 2023, key agencies including the National Anti-Corruption Commission (NACC), Office of the Public Sector Anti-Corruption Commission (PACC), and the Office of the Auditor General collectively used 5.848 billion baht and employed over 7,578 personnel. This reflects the high national cost of addressing deeply rooted corruption in the bureaucracy.

These statistics reveal that corruption is deeply entrenched and persistent, preventing complete eradication and forcing citizens to live amid ongoing corruption.

The National Anti-Corruption Commission’s 2024 fiscal year report shows a record high of 11,662 corruption complaints, a 19.47% increase over the 2019–2023 average. Approximately 84.49% of allegations were forwarded from agencies responsible for overseeing state power usage, such as the Royal Thai Police, Public Sector Anti-Corruption Commission, Department of Special Investigation, and the Office of the Auditor General.

Between 2019 and 2024, the NACC has considered and found guilt in 3,700 cases, with local administrative organizations being the most accused at 1,550 cases, followed by the Ministry of Interior with 375 cases, Ministry of Education with 198, and other government agencies totaling 1,265 cases. This concentration highlights that corruption is clustered in agencies managing budgets closely related to the public. Currently, the NACC has 1,527 ongoing cases under investigation.

This data indicates that corruption in Thailand continues to rise, both in complaint numbers and workload for oversight agencies. Case reviews and verdicts face limitations in time and resources, posing significant challenges to effective corruption suppression and long-term public trust-building.

Mr. Mana Nimitmongkol, Chairman of the Anti-Corruption Organization (Thailand), proposed a solution involving civil society and the business sector jointly establishing an “Anti-Corruption War Room.” This would include representatives from various sectors such as senior politicians, ministers, deputy prime ministers, and academics, demonstrating government commitment to fighting corruption. The war room would function as a concrete mechanism to oversee state power use, with authority to review and demand relevant documents, especially in cases of major policy changes or significant government power use. If effectively implemented, this could boost public confidence in the government.

Regarding penalties, Mr. Mana emphasized the need for swift action once offenders are identified and genuine enforcement of prison sentences. He proposed that offenders serve at least two-thirds of their sentenced prison time before eligibility for royal pardon or sentence reduction. Currently, corruption cases often apply the same sentence reduction rules as general prisoners, requiring only one-third of the sentence served. These enforcement measures must adhere strictly to human rights and judicial due process.

Although Thailand continues to face persistent and worsening corruption issues, the public still hopes the government will demonstrate genuine commitment to addressing them. The staggering losses from corruption highlight not only vast financial damage but also deep-rooted structural problems in bureaucracy and governance. With complaints and corruption cases rising steadily, the main challenge lies not merely in prosecuting individual cases but in overhauling systems, strengthening oversight mechanisms, and fostering genuine transparency.

The proposal to establish an anti-corruption war room alongside stricter, fairer penalties under human rights principles could be a vital starting point to restore public trust. If the government shows sincere determination and concrete action, tackling corruption may become not just a distant hope but the first step toward the long-awaited change Thai society desires.