The Equitable Education Fund (EEF) reveals five key findings reflecting the crisis in Thai education, where unequal starting points for children risk leaving them behind global trends and abandoned.

Thailand is entering another general election season, with political parties presenting policies to garner votes, among which “education policy” is a crucial factor that citizens—especially parents and newly eligible young voters—consider when deciding which party to support for government.

Historically, the Ministry of Education has been regarded as one of the "Grade A ministries" due to its large budget of several hundred billion baht annually and its key role in national development through human capital development. However, when looking at Thai education, it is undeniable that many critical problems remain unresolved or have not progressed sufficiently. Issues such as outdated curricula that do not keep pace with the world, graduates unable to find employment, and educational opportunity inequalities persist. These problems are exacerbated by economic challenges like Thailand's low GDP growth of 2-3% per year, widespread poverty and household debt, and demographic structural issues, leading to what can be described as a "low birthrate, aging, and impoverished society."

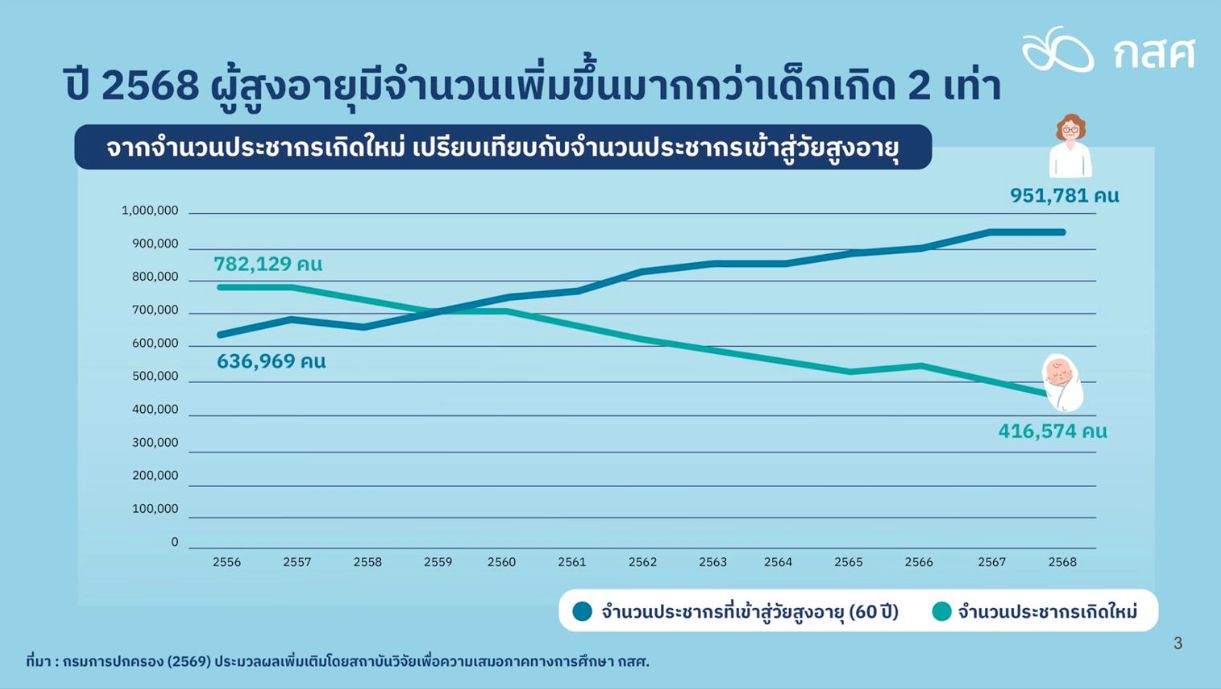

Thailand entered a complete aged society in 2023, with over 20% of the population aged 60 and above, and is moving toward a super-aged society with more than 28% elderly population, the fastest rate in ASEAN.

An increasing elderly population means rising fiscal burdens, while the number of newborns—future working-age taxpayers—continues to decline worryingly. In 2025, the elderly population will increase by 951,781 people, double the number of newborns, which will be only 416,574.

Moreover, the number of poor households continues to rise from 686,000 in 2023 to 1.03 million in 2025. This situation makes "every Thai child" born in this era extremely valuable— a "golden human resource" that is scarce and critical for Thailand’s future, and education is the most important tool to prepare these children for the future.

However, the latest report from the Equitable Education Fund (EEF) reveals five major findings that reflect the reality and obstacles holding back Thai education from fulfilling this role fully.

Although education is a basic right provided by the state, limitations still cause learning standards to vary across schools. Combined with individual "starting points"—including financial resources and environment—children from better-prepared families have greater access to quality education. Data from various assessments show that unequal "human capital" widens educational disparities among Thai children. The National Educational Test (O-NET) results for grade 6 in academic year 2024 indicate that children in small schools, which comprise more than half of all schools nationwide, often face resource shortages. Most students come from poor or disadvantaged backgrounds and score lower than those in medium and large schools across all subjects, especially

English. . Meanwhile,

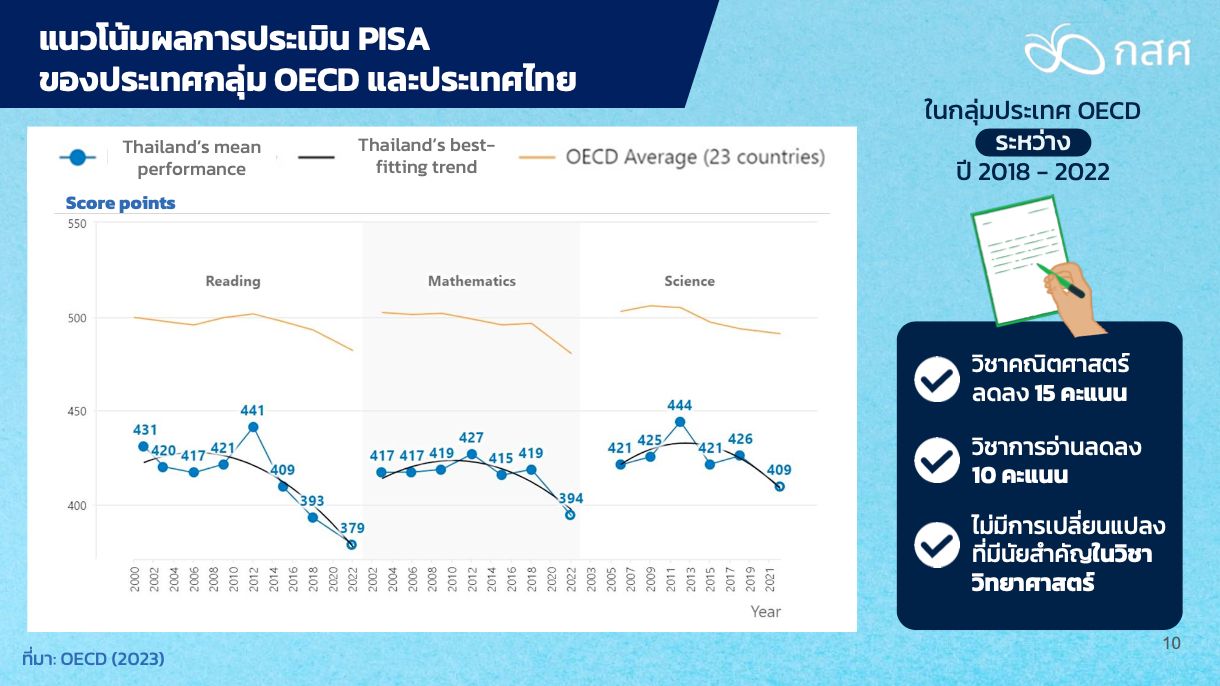

the results of the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) in 2022, which tested 15-year-old students, showed rural children lag behind urban peers by three school years in math, science, and reading. The saddest truth is that poor children have very limited access to higher education, which is crucial to breaking the

"cycle of persistent poverty." Tracking data for students from the poorest 15% of households who graduated grade 9 in 2022 (167,989 students) found only 81.5% continued to upper secondary school. At the tertiary level, the number drops sharply to just 12.5%, or 21,079 students.

Meanwhile, the national university admission rate through the TCAS system is 32%, indicating that poor children have 2.5 times fewer chances to enter university than their peers. 2. Thai Human Capital Lags Behind ASEAN Neighbors and the World Not only domestically but also internationally, various assessments indicate that

lack essential “future skills” and risk falling behind in the globalized world where everyone is a global citizen driven by advanced science, technology, and innovation, especially artificial intelligence (AI). Reviewing PISA results over the past 20 years reveals a continuous decline in Thailand’s scores over the last decade. Basic skills are below the OECD average and behind many ASEAN neighbors such as Singapore, Malaysia, and Vietnam.

In particular, specialized skills like global competence, the ability to understand global issues and collaborate across cultures—a critical skill in today’s borderless communication world—place Thailand 21st out of 27 countries assessed, indicating low readiness to adapt to global trends.

Another crucial skill, creative thinking, which underpins innovation and economic progress, also ranks low, with Thailand at 51st out of 61 countries, behind ASEAN neighbors including Singapore, Malaysia, and Brunei.

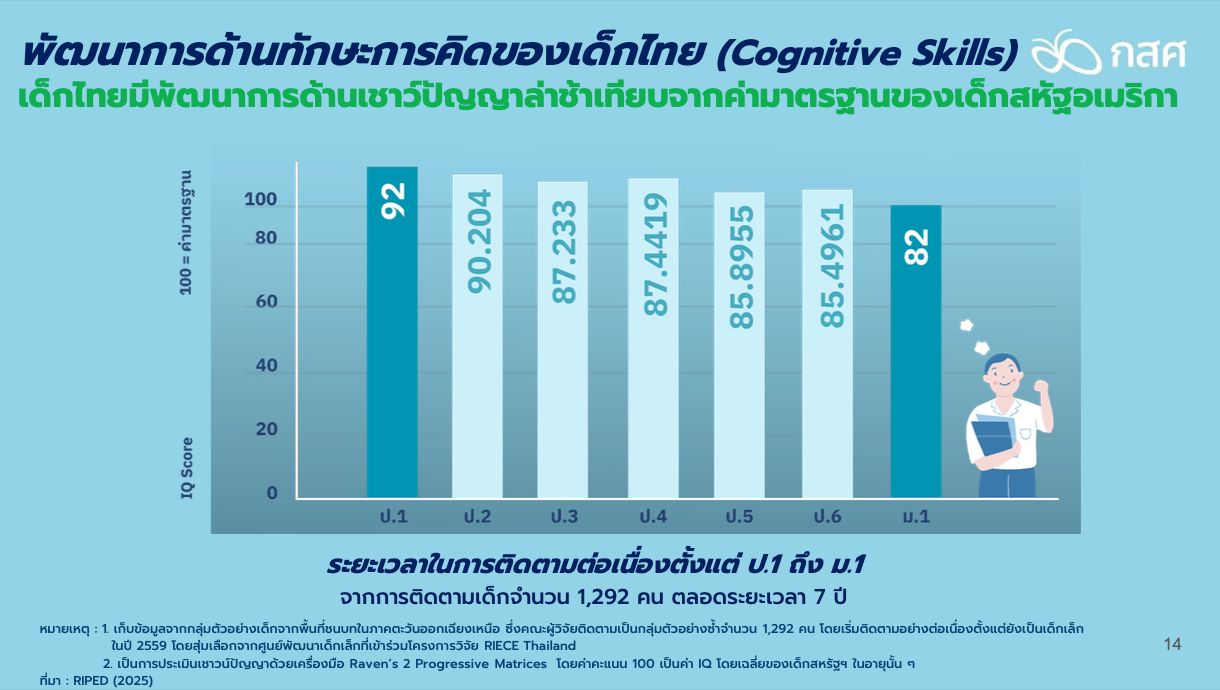

3. Inflexible Education System Leads to Decline in Thai Students’ Thinking Skills Normally, accumulating knowledge and experience should increase expertise, but research by EEF and the Research Institute for Policy Evaluation and Design (RIPED) at the University of the Thai Chamber of Commerce found that Thai students become less intelligent as they advance in school. Tracking a sample group of rural children from early childhood through grade 7 revealed their average IQ is below the U.S. average of 100 for that age, with a downward trend—from an average IQ of 92 in grade 1 to just 82 in grade 7.

education system is inflexible,

failing to adapt to children's interests, causing boredom and loss of motivation. Poor exam results may lead to dropping out of school altogether. 4. Education System’s Inflexibility During Crises Worsens Its Unpreparedness In recent years, Thailand has faced multiple crises, including natural disasters and international conflicts, disrupting children’s education in many areas. For example, the southern floods in November 2025 forced the closure of 822 schools, affecting nearly 100,000 students. Recovery of school buildings and materials took time.

Similarly, ongoing Thai-Cambodian border conflicts repeatedly disrupt education in seven border provinces. In the latest flare-up in December 2025, over 1,168 schools closed and switched to online learning, mostly affecting already disadvantaged children. During conflict, parents struggle to earn livelihoods or must evacuate to shelters, lacking access to devices and internet, and facing unsuitable learning environments. This leads to "learning loss,"

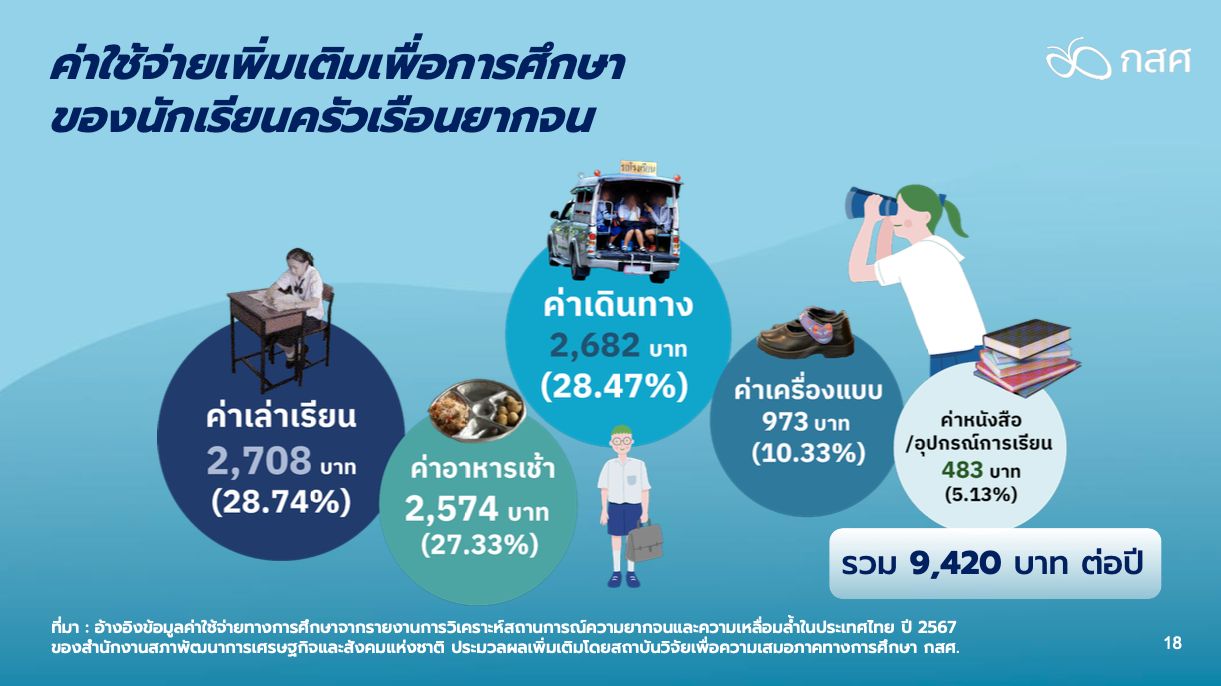

5. Thailand’s “Free Education” Is Not Truly Free Although Thailand has a "Free 15 Years of Education" policy, with government per-student subsidies and funding from EEF, the funds are insufficient. Poor households still pay an average of 9,420 baht per year out of pocket. Moreover,

the uniform per-student subsidy may sound equitable but does not reflect real conditions and violates the principle of "vertical equity,"

Therefore, under-resourced schools should receive higher subsidies according to their needs to ensure all schools operate efficiently and equitably. In fiscal year 2021, out of every 100 baht spent on education, only 22 baht was allocated to educational equity. Breaking this down, 18 baht supported horizontal equity—equal payments to all children for programs like free education and lunch—while only 4 baht went toward vertical equity to reduce disparities for disadvantaged children, which is insufficient to close gaps in Thailand. From the "Pit" to the Way Forward: What Can We Do?

These five findings show that Thailand is stuck in developing human capital with resource allocation inequalities. The government, private sector, and citizens must collaborate to make changes. 1. Develop human capital to be both “equal” and “future-ready.” Invest in advanced thinking skills and competencies needed for the future through flexible learning methods emphasizing analytical thinking over rote memorization, with systems to monitor and assist students, ensuring no one is left behind. 2. Allocate resources fairly to make “free education” a reality. Provide subsidies for hidden costs based on each group's needs. Reform budget allocation to schools according to actual costs, increasing funds for small remote schools with higher per-student expenses, with an estimated additional government subsidy of about 55 million baht.

3. Create a flexible and crisis-resilient education system.

Improve educational infrastructure to withstand disasters or unexpected events, with actionable contingency plans ensuring continuous learning even when schools must close.

the nation’s most valuable "golden human resources,"

to grow in step with global trends and lead Thailand forward toward achieving developed country status successfully.